Man Buys Historic Bank For $1, Transforms Into Architectural Marvel

Chicago’s first-ever Architecture Biennial served as a staging ground for wild pavilions, exhibits, and installations. The fair also coincided with the debut of a major new artwork: the Stony Island Art Bank.

Theaster Gates bought the Prohibition-era Stony Island Trust & Savings Bank building from the city of Chicago for $1. Yes, there was a catch: The artist had to raise the $3.7 million it would take to rehabilitate the building and put it to new use. Gates did the thing that you’re never supposed to do with a historic building: He started pulling it apart, piece by piece.

Since 2013, Gates has been pulling chunks of marble from the building. The artist cut these chunks into “bond certificates” stamped with his signature and the motto, “In ART We Trust.” As Gates told The New York Times back in 2013, he sold 100 marble tablets for $5,000 apiece, as well as some larger slabs that went for $50,000 each. Since they’re artworks whose value stands to appreciate, the marble chunks in fact do work like bonds.

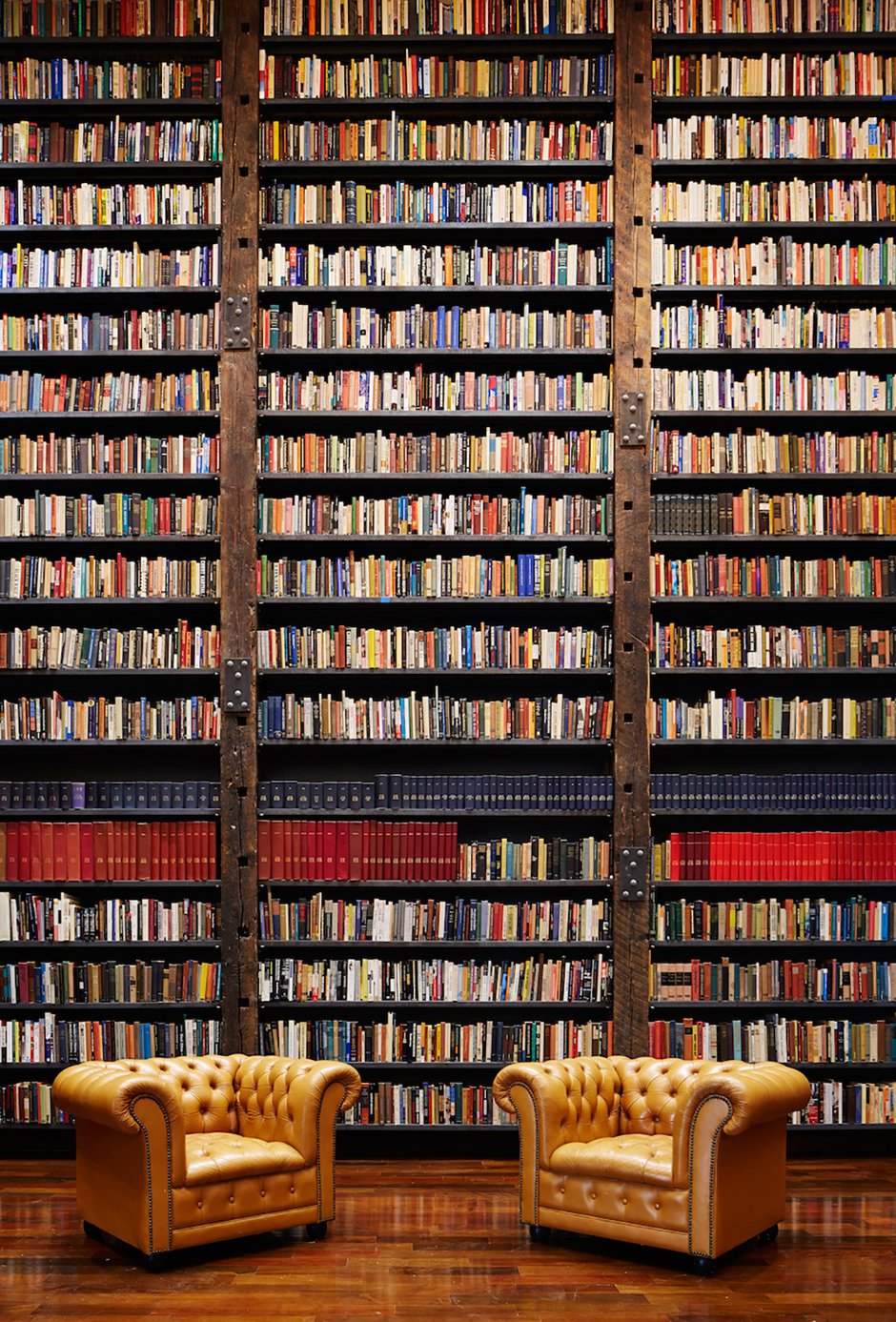

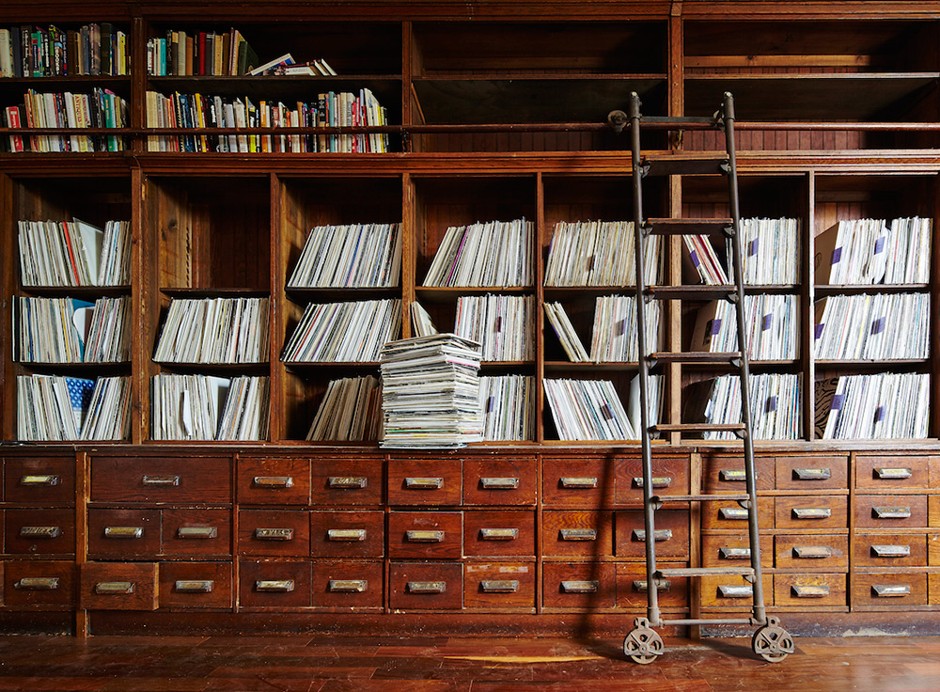

All of Chicago’s South Side was invited to attend the opening of the Stony Island Art Bank earlier this month. (Chicago Architecture Biennial attendees, too.) The building is now an archive for community resources, among them the books and magazines of John H. Johnson, founder of Ebony and Jet and the vast record collection of Chicago’s Frankie Knuckles, the late Godfather of House Music.

“The concept floats across: this place is about access,” writes Ari Ephraim Feldman in South Side Weekly, noting that the opening was filled with Motown music and dancing as well as a cardboard installation by the Portuguese artist Carlos Bunga.

Tom Harris/Hedrich Blessing (courtesy of Rebuild Foundation)

Typical Gates. The artist is known for his work in a field called “social practice,” a genre that has no specific medium or form—only an ethos about working with communities or institutions. The lineage of this kind of work is long and distinguished, although in recent years, social practice has gained traction and visibility beyond the art world. Mel Chin, a sculptor, has made work directly engaging the plight of lead-soil contamination in New Orleans. Rick Lowe—who rejects the term—won a MacArthur Foundation genius grant for Project Row Houses, an incubator and community resource center in Houston comprising 22 formerly derelict properties. (Lowe refers to his work as “social sculpture,” for what it’s worth.)

Feldman’s writeup of opening night captures an important dynamic in Gates’ work. “I talked to people at the opening, and the general pattern was this: if you had a ticket you were inspired, and if you had a uniform on you were confused,” he writes. Feldman elaborates:

Ticket: “I love that he’s preserving this music for the younger generations to come and listen to it.” Uniform: “It’s unique. Different. Good for the neighborhood, I guess.” Ticket: “They’re taking depleted buildings in the community and returning them to the jewels they are.” Uniform: “All I know is that it used to be an abandoned building and now it’s not.” Ticket: “This space is multifunctional—it’s just a space waiting to activate.” Uniform: “I don’t know what […] this place is for.”

It’s an insightful observation. The decidedly different ways that people of different stripes relate to the project is what gives it its great dimensionality. It’s one factor that distinguishes the Stony Island Art Bank as an artwork, not just an arts venue. The same goes for the other South Side projects that Gates is creating through his Rebuild Foundation.

In a release, Gates described the project as “an institution of and for the South Side.” The New Yorker says that Gates is “is reshaping the South Side in his image.” That’s not quite right (I say, having never met the man). To my mind, Gates is just teeing up the South Side. It’s the people who complete his installations. The bonds he sold are an investment in them.

Tom Harris/Hedrich Blessing (courtesy of Rebuild Foundation)

Tom Harris/Hedrich Blessing (courtesy of Rebuild Foundation)

Tom Harris/Hedrich Blessing (courtesy of Rebuild Foundation)

Tom Harris/Hedrich Blessing (courtesy of Rebuild Foundation)

Tom Harris/Hedrich Blessing (courtesy of Rebuild Foundation)

Tom Harris/Hedrich Blessing (courtesy of Rebuild Foundation)

Tom Harris/Hedrich Blessing (courtesy of Rebuild Foundation)

via CityLab

No Comments